Friday, January 27, 2006

News Flash -- I'm an idiot!

I've completely misunderstood yi quan's three fists. I thought that stamping fist (which I can't find any links to, so maybe the name was mistranslated) was an inertial transfer, but that's totally wrong. Sifu Fung was absolutely right when he kept calling "battering ram method" not part of the way things were supposed to work. I didn't put two & two together at the time, but it's very simple: you can't hit someone via gravity transfer when your inertia is settled ("when your energy is sink" as he would have said) -- it's already at rest, so there's no potential to transfer. Whatever my old "gravity hit" was, it isn't yi quan. Urg, sometimes I feel like such a maroon! I'll take some of that humble pie now thank you.

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

East vs. West w/ extra-credit religion

I had an interesting conversation w/ my brother on the telephone last night, in which, in addition to discussing yi quan and xing yi, we batted back & forth our ideas of what the differences between the Orient and Occident really were. (I'm using the terms Orient vs. Occident instead of East vs. West because it makes the regions more clear -- we weren't including, for example, the Turkic or Russian worlds.) I told him about my Zen teacher's statement that the West parameterizes things in terms of time while the East parameterizes things in terms of space, and Russ proposed that the Occident is primarily underpinned by philosophy, specifically that there should be a philosophy for everything. For example, the question "Is punk dead?" harrows the souls of people who would otherwise just listen to music and get stoned, not the kind of folks you normally think about tagging with the term "philosopher". We have sports-ology, musicology, even ology-ology. He proposes, and I agree, that this stems from the fundamental question of the Occident: "What happened?", with it's inherently narrative basis. He further proposed that perhaps the fundamental question of the Orient is "What's up?". It seems to me that while "what's up?" sufficiently avoids the narrativity of the Occident, it doesn't fully capture why the Orient is so much more concerned with function over mechanism and correllation over causality. So instead I'd like to humbly proffer the following fundamental question of the Orient:

How does all of this stuff relate to each other, or, what does this have to do with that?

This also helps to explain how the Orient was able to come up with the Buddhist insight, aka "what do you mean other?" "Other" makes perfect sense within a narrative hermaneutic, but from the perspective of interbeing and relation it only makes sense as a working assumption, one that rapidly falls apart upon examination. Also interesting (perhaps only to me?) is that two out of three of my theological guideposts, namely the doctors John of the Cross and Catherine of Sienna (but not Thomas a Kempis, or, at least not in Imitation of Christ, which was the principle work of his I followed), in naming God "WHO AM" point directly at an interessential hermaneutic, albeit not the one the Buddhists derived from their Hindu forebears. It raises an interesting extra-credit question:

How much of Buddhist practice & philosophy is not only compatible with, but in direct accord with Catholicism?

If, as Karl Rahner said, God is, among other things we may know nothing about, the Fundamental Ground of All Being, where "All Being" is inherently singular, then working to understand the non-duality of nature is part and parcel of seeking to understand creation. Given how Buddhist practice, by helping one to directly perceive non-duality, is very helpful for following the second Great Commandment, someone who, unlike me, has any faith at all to speak of, might be able to make good use of it as a part of their Christian, um, practice? uh, behavior? uh, whatever you'd call it. Not as I do, with "hmm, the 2nd Great Commandment is cool, that should be included", but as a real Christian aught, with this part of a fully God-centered, worshipful program.

How does all of this stuff relate to each other, or, what does this have to do with that?

This also helps to explain how the Orient was able to come up with the Buddhist insight, aka "what do you mean other?" "Other" makes perfect sense within a narrative hermaneutic, but from the perspective of interbeing and relation it only makes sense as a working assumption, one that rapidly falls apart upon examination. Also interesting (perhaps only to me?) is that two out of three of my theological guideposts, namely the doctors John of the Cross and Catherine of Sienna (but not Thomas a Kempis, or, at least not in Imitation of Christ, which was the principle work of his I followed), in naming God "WHO AM" point directly at an interessential hermaneutic, albeit not the one the Buddhists derived from their Hindu forebears. It raises an interesting extra-credit question:

How much of Buddhist practice & philosophy is not only compatible with, but in direct accord with Catholicism?

If, as Karl Rahner said, God is, among other things we may know nothing about, the Fundamental Ground of All Being, where "All Being" is inherently singular, then working to understand the non-duality of nature is part and parcel of seeking to understand creation. Given how Buddhist practice, by helping one to directly perceive non-duality, is very helpful for following the second Great Commandment, someone who, unlike me, has any faith at all to speak of, might be able to make good use of it as a part of their Christian, um, practice? uh, behavior? uh, whatever you'd call it. Not as I do, with "hmm, the 2nd Great Commandment is cool, that should be included", but as a real Christian aught, with this part of a fully God-centered, worshipful program.

Friday, January 20, 2006

Morocco attempting moderate Islam

As owner of the ironic nickname "St. James the Apostate", everyone knows my loving hatred of religion (you can debate whether or not Buddhism is a religion), but since I don't have any really good ideas as to what else can fulfill religion's role in civilized societies (instead of its pernicious role in blood-thirsty ones), it's good to see that folks like King Mohammed VI are trying very hard to keep the proverbial baby instead of the co-proverbial bathwater that the Wahabbists embrace.

As owner of the ironic nickname "St. James the Apostate", everyone knows my loving hatred of religion (you can debate whether or not Buddhism is a religion), but since I don't have any really good ideas as to what else can fulfill religion's role in civilized societies (instead of its pernicious role in blood-thirsty ones), it's good to see that folks like King Mohammed VI are trying very hard to keep the proverbial baby instead of the co-proverbial bathwater that the Wahabbists embrace. Imagine an Islamic state in which:

- Women don't live in fear.

- The King calls himself First Among Equals.

- Democracy & self-determination instead of kleptocracy is the order of things.

PS. I'm now putting my links in pictures where available, so when you don't see a link try the image.

Thursday, January 19, 2006

Thursday, January 12, 2006

Shrub was right on Kyoto!

For years now, Shrub has been being blasted for his response to the Kyoto Treaty: "let's wait for the science to be better". The rest of the world (except for China) laughed at his obvious unfriendliness to the environment, and put ratified Kyoto. Now, part of the basic underpinnings of the treaty, namely the idea that "carbon sinks", aka big amounts of leafy greenery, offset industrial pollution has been shown to be wrong. It turns out that while green plants mitigate the presence of carbon dioxide, they account for 20 to 30 percent of annual methane production, and will account for more as the temperature rises. This doesn't mean that plants are bad, nor that global-warming isn't happening, but it means that Kyoto's basic ideas as to how to fix the problem are bogus. Three cheers for Shrub -- he got something right!

Wednesday, January 11, 2006

The Coming Darkness

In what has to be one of the most depressing articles I've read in a while, Mark Steyn of "The New Criterion" (which appears to be a Conservative journal of some sort) has penned an essay entitled "It's the demography, stupid", in which he twists around Clinton's anthem into a dire assessment of the future of the Western World.

According to Steyn, it hasn't got one. His reasoning is very simple:

Dark indeed.

* Under Sharia, a rape victim needs to find four male witnesses to testify on her behalf, otherwise seeking justice opens her up to indefensible slander charges, since as a woman her testimony doesn't count. It's worse if she gets pregnant: if she does, then that's proof of adultery & she's stoned or hanged -- or, if she's lucky enough to live in a country with "liberal", "tolerant" Islam, she gets to suffer 100 lashes.

According to Steyn, it hasn't got one. His reasoning is very simple:

- Western societies are busy putting their resources into comforts for the aged instead of sustaining their populations.

- Western societies are making up the population differences via immigration.

- Western societies, in order to be multi-culti &c, are tolerating the intolerance of immigrant populations, especially the intolerances endemic to Islam, rather than forcing them to adopt the "native" culture.

- As a result of reproduction rates anywhere from 1.1 to 1.87, mostly on the low end (with the U.S. as a temporary stand-out at 2.07, thanks mostly to Mexican Catholics), the proportion of Western societies which value Western values, especially human rights, democracy and the rule of law, is declining -- inexorably declining for Europe, whose highest "native" reproduction rate is 1.5 and falling.

- As a result, within one or two generations, most of Western societies will be populated by people who actively disdain all that the West stands for. When even in England, the majority of Muslims want to live under Sharia, you know that doesn't auger well for anyone.

Dark indeed.

* Under Sharia, a rape victim needs to find four male witnesses to testify on her behalf, otherwise seeking justice opens her up to indefensible slander charges, since as a woman her testimony doesn't count. It's worse if she gets pregnant: if she does, then that's proof of adultery & she's stoned or hanged -- or, if she's lucky enough to live in a country with "liberal", "tolerant" Islam, she gets to suffer 100 lashes.

Why Buddhism must change in the West

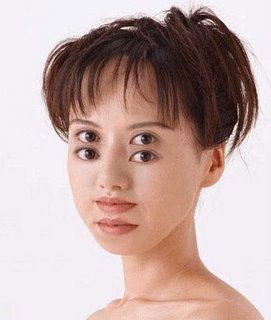

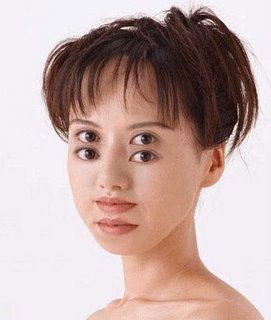

Here I offer you a very simple illustration of why Buddhism in the West will become its own school. Let your mind drop into low gear, then look at the following picture, that's been making the rounds on the web lately:

What's going on here? The internal dissonance you're feeling isn't due to any artifact of mind at all; it's purely a result of the established mechanisms by which your brain works. This is important, because it illustrates that while the West has a lot to learn about why what it knows is important*, it also directly shows how the philosophy of the East needs to learn to incorporate mechanisms beyond functional analysis. The functional analysis of the East is fantastic, yielding ideas such as the widely misunderstood term "chi", that the West could never have come up with. Sadly, though, it has its own inherent blinders. A Buddhist might tell you that fundamentally, "all [is] consciousness". The Tibetan Buddhists go so far as to make this an actual cosmological statement. But, "all consciousness" is only true from the perspective of consciousness. It's like trying to understand chemistry when your only instrument is a Geiger counter -- it doesn't lie, but it doesn't tell you the truth either. Nothing in Buddhism will tell you what's happening to you when you see this picture (although it can speak to what happens to you when you react to what happens when you see the picture), but works of modern cognitive science such as Dennett's "Multiple Drafts Hypothesis" (which I happen to think is correct) can do so.

East and West have much to learn from each other. For Western students of Buddhism, this means that while it's important to read the sutras, it's also important to read Western philosophy as well. Sure, it's full of dualisms and often misses the point; but it also speaks on subjects outside the purview of observation, and thus accesses wisdom that we can ill afford to do without.

* I had an interesting conversation with my brother on Christmas in which I stated my discovery of the general truth "the experience of mind is the same". His reaction, as a student of Western history & philosophy, was "duh, we've known that for centuries". There's a lot that the West knows, but that it may not realize is terribly important. In this example, this little truth may not be seen as widely important to Western audiences given the applications of the time, but to a Buddhist, it's one of the "Keys to the Kingdom", if you'll pardon the metaphor.

What's going on here? The internal dissonance you're feeling isn't due to any artifact of mind at all; it's purely a result of the established mechanisms by which your brain works. This is important, because it illustrates that while the West has a lot to learn about why what it knows is important*, it also directly shows how the philosophy of the East needs to learn to incorporate mechanisms beyond functional analysis. The functional analysis of the East is fantastic, yielding ideas such as the widely misunderstood term "chi", that the West could never have come up with. Sadly, though, it has its own inherent blinders. A Buddhist might tell you that fundamentally, "all [is] consciousness". The Tibetan Buddhists go so far as to make this an actual cosmological statement. But, "all consciousness" is only true from the perspective of consciousness. It's like trying to understand chemistry when your only instrument is a Geiger counter -- it doesn't lie, but it doesn't tell you the truth either. Nothing in Buddhism will tell you what's happening to you when you see this picture (although it can speak to what happens to you when you react to what happens when you see the picture), but works of modern cognitive science such as Dennett's "Multiple Drafts Hypothesis" (which I happen to think is correct) can do so.

East and West have much to learn from each other. For Western students of Buddhism, this means that while it's important to read the sutras, it's also important to read Western philosophy as well. Sure, it's full of dualisms and often misses the point; but it also speaks on subjects outside the purview of observation, and thus accesses wisdom that we can ill afford to do without.

* I had an interesting conversation with my brother on Christmas in which I stated my discovery of the general truth "the experience of mind is the same". His reaction, as a student of Western history & philosophy, was "duh, we've known that for centuries". There's a lot that the West knows, but that it may not realize is terribly important. In this example, this little truth may not be seen as widely important to Western audiences given the applications of the time, but to a Buddhist, it's one of the "Keys to the Kingdom", if you'll pardon the metaphor.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)